Turn left.

Turn left.

Turn left.

Turn left.

Turn left, the softly spoken female voice repeated with infinite patience through the headset in my helmet. I had the volume set to maximum so that I could hear her instructions through the foam ear-plugs I always wear: squishy three-quarter inch orange slugs rolled between my thumb and index finger into a compressed noodle which I slid carefully, with practiced precision, down my ear canal where they then expanded to form a barrier between my ear drums and the thundering wind noise that crashed into my helmet.

Turn left.

Her voice, muffled but discernible, passed through the compressed foam.

At other times her voice would come to me like a calming spirit. In the interminable grid of city streets bearing unfamiliar and likely unmarked names, where nature’s geography was subsumed by tall gray buildings, I welcomed her familiar presence. Bodiless, all-knowing, patient, she guided me through the urban wilderness. In those times, I could not imagine a journey without her there to lead me by the handlebars.

Turn left.

I heard no malice in her voice, though I ignored her persistent demands.

Turn left.

I looked ahead, over the handlebars I gripped slightly too tightly, over the analogue instrument panel and the black plastic fairing, over the dusty, unmarked, and unpaved tracks that snaked in a slow wave from the left to right to left to the horizon. There was no road there, per se, though thousands of people undoubtably made this punishing trip every year, each following his intuition or experience to point his Toyota Landcruiser with his six or seven cramped and nauseated passengers down this or that rut. Some pioneering drivers blazed new routes over the sand and rocks. Their fresh treads were visibly lighter than the surrounding desert. Shallow and unproven, they were not yet carved by friction and repetition into the infinite modulation of low humps that crush bearings, suspensions, and spirits.

Perhaps the spirit in my headset, the one with the gentle voice who whispered in my ear, was crushed as well. Did she realize that she was not useful here, that she could not soften the blows of this pounding road? That being lost here would be better resolved by heeding the direction of the shadow of the sun than by close adherence to the blue line illuminated on my phone?

Perhaps, beneath her placid voice, within the soul of her circuitry she was angry.

Turn left.

In the three days it took us to cross the 504 km in the infamously remote region of Southwestern Bolivia known as The Lagunas Road, or simply as The Southwest Circuit, we tested our mettle and the mettle of our bike against punishing washboard roads, deep sand, scattered rocks, steep climbs, rain, cold, water crossings, and unrelenting wind. Everything was exacerbated by the extreme altitude, over 4,000 meters above sea level. When we started our Pan-American trip and indeed even up to several months prior, we did not entertain the idea of crossing this challenging terrain, let alone by ourselves. A week prior to setting out, we had camped at the town of Tupiza near the site where Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid ran out of luck, and less than 100 km from Argentina, and debated whether to cross the border and forego the Lagunas Route or return north, zigzagging into Chile and adding a couple of weeks to our itinerary.

We opted to return to Uyuni and the salt flats, the departing point for the Lagunas Road.

We had already visited Uyuni several weeks earlier and ventured out deep into the legendary salt flats that make the town famous. The salt was still dry then, though the rains were coming, and we camped by an island of rock puncturing the endless whiteness and populated with large hairy cacti. The wind battered our tent until late in the night, turning the wall into an inverted parabola by its force. In the dusky evening, we gathered rocks from the island and stacked them against the motorcycle to buffer its assault on our fragile abode, but to little avail. It wasn’t an environment welcoming to human visitors nor indeed to any but the most hardy of life. As the sun set, the sky glowed in every direction with indescribable hues of purple and turquoise and orange, like a bowl of rainbow sherbet spilled across the horizon. As darkness enveloped us, the world became even more surreal. The salt practically glowed as it reflected the light of the moon.

When we returned several weeks later, however, the rains had begun. The entrance to the salt flats was like a shallow lake and over much of the surface of the salt a thin film of water, only an inch or two or three deep, reflected the sky and the clouds like a massive natural mirror. Many visitors come to Uyuni simply to see this mirror effect with their own eyes. We decided, perhaps unwisely, that we could not pass up the chance to see it ourselves and rode Horace out onto the salt flats for a second time. The sight was magnificent, but salt is horribly corrosive to metal, grease, electrical components, and pretty much everything else on a motorcycle.

Upon returning from the salt flats, and after giving Horace a high-pressure bath, and then drying out a damp airbox, we set out for the Lagunas Road.

Turn left.

The world around us was more foreign than any city is capable of being, but she was of no use. The sand seemed unpredictable in its variation. From red to green to yellow, we saw the entire landscape transformed. We felt like ants roaming over a box of crushed crayons. The mountains plunged upward into the sky around us, dominating the fantastic terrain.

She displayed, as visual reference, a thin blue line indicating the direction I should have been heading and an arrow indicating that I was riding perpendicular to that line. Somewhere, no doubt, beyond the edge of the screen there was a road we should have been on. If we followed her guidance we would have eventually found a road through this desolate wilderness that would guarantee our arrival at some distant destination.

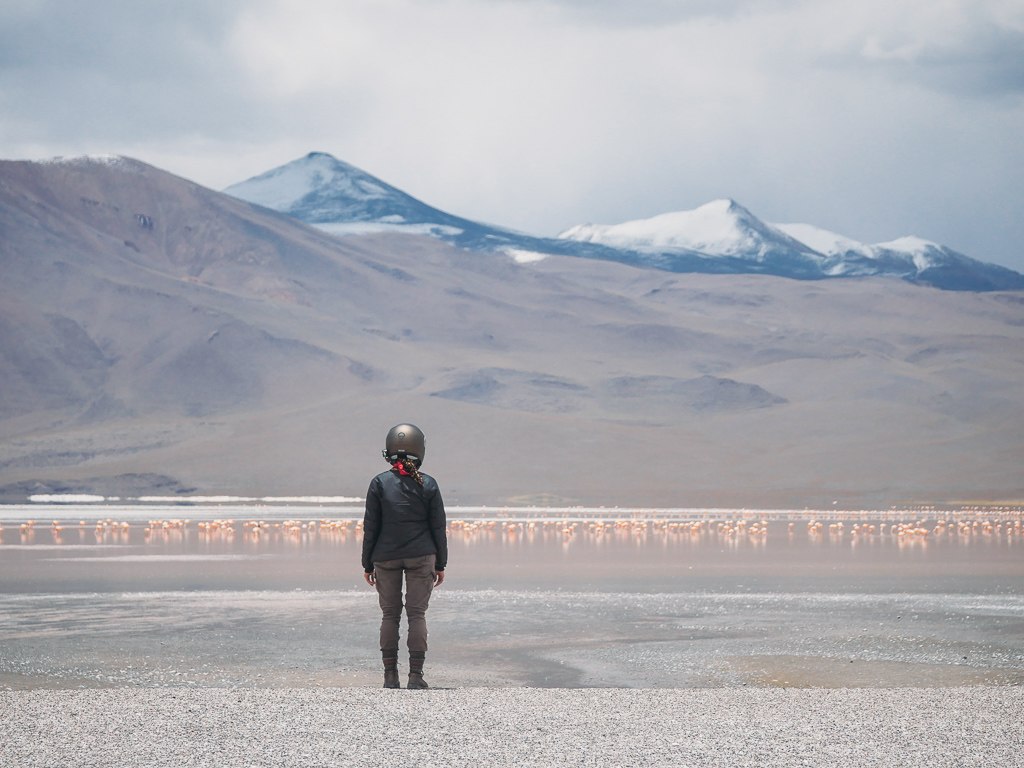

But I ignored her. I was distracted by a sight up ahead. Beneath lavender mountains, a shallow clay-red lake splayed out, and within it, propped on yellow stick-like legs, stood thousands of fluorescent pink Andean flamingoes.